- Left: Ukrainian soldiers and firefighters search in a destroyed building after a bombing attack in Kyiv, Ukraine, Monday, March 14, 2022. PhotoCredit@AP 写真左:2022年3月14日(月)、ウクライナのキエフで爆破攻撃を受け、破壊された建物内を捜索するウクライナ兵と消防士。

- Right: Photo by Chin Twin Chit Thu taken on February 3, 2022 shows an aerial photo of burnt buildings in Sagaing Division, where more than 105 buildings were destroyed by junta military troops, according to local media. PhotoCredit@Chin Twin Chit Thu 写真右: 2022年2月3日に撮影されたサガイン地域の焼けた建物を写した航空写真。地元メディアによると105以上の建物が軍事部隊によって破壊された。

This is a commentary by professor Zackary Abuza recently posted on RFA (Radio Free Asia: a private, nonprofit corporation, funded by the U.S. Congress through the U.S. Agency for Global Media). Below is a slightly edited version and its Japanese translation.

RFA (Radio Free Asia:米国連邦議会の資金援助を受け、米国グローバル・メディア・エージェンシーを通じて設立された非営利の民間企業)に掲載されたザカリー・アブザ教授の解説を一部省略し和訳で紹介します。

Both Russia and Myanmar intentionally target civilians, apartments, and hospitals and block humanitarian convoys

ロシアでもミャンマーでも 意図的に民間人、住居、病院を標的にし、人道的輸送隊を妨害している

As the war in Ukraine drags on, with no clear-cut Russian victory in sight, we are seeing important parallels with the conflict in Myanmar, which has fallen from the headlines.

The Russian offensive in Ukraine has faltered, and there has been a heavier reliance on indiscriminate air attacks with non-precision guided munitions and artillery. The Russians don’t have sufficient forces to capture and hold cities, so they surround them and use long-range artillery fire.

They are intentionally targeting civilians, apartment blocks, and hospitals. Like Myanmar’s military, Russian forces have laid siege and prevented humanitarian convoys from reaching civilians. There can be no pretense that this is simply collateral damage.

ウクライナ戦争が長引き、ロシアの明確な勝利が見えない中、見出しから消えてしまったミャンマーの紛争との重要な類似性が見えてきた。

ウクライナでのロシアの攻撃は頓挫し、非精密誘導弾や大砲による無差別空爆に頼ることが多くなっている。ロシアは都市を占領・保持するだけの戦力がないため、都市を包囲し、長距離砲撃を行うのである。

民間人、集合住宅地、病院を意図的に狙っている。ミャンマー軍と同様に、ロシア軍は周囲を包囲することで人道的支援が民間人に到達するのを防いでいる。単なる巻き添え被害だと言うことはできない。

Right: A protester holds onto the shirt of a fallen comrade, during a crackdown by security forces on demonstrations against the military coup, in Yangon, March 14, 2021. PhotCredit@AFP 右。2021年3月14日、ヤンゴンで、軍事クーデターに反対するデモに対する治安部隊の弾圧中、倒れた同志のシャツにしがみつくデモ参加者。

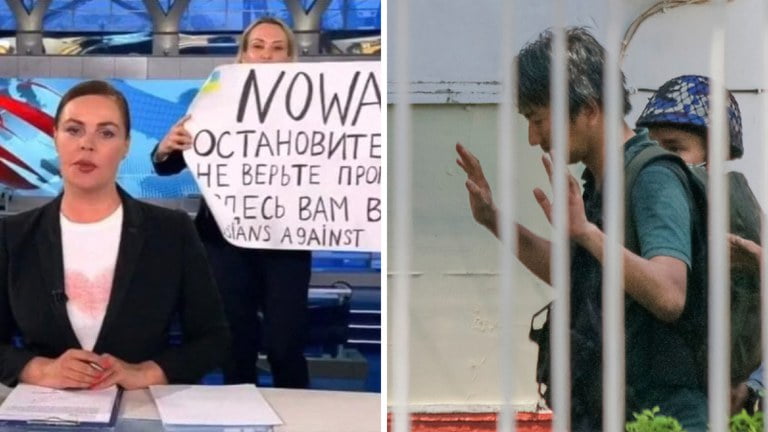

Both regimes have stepped up arrests of dissenters

両政権とも 異論を唱える人々の逮捕を強化している

Both Russia and Myanmar rely on poorly trained, conscript militaries, with low morale. As Russian forces have been depleted through deaths, injury or desertion, we are seeing the leadership call up mercenaries from Chechnya, Syria, and their own Wagner Group, a Russian paramilitary organization. In Myanmar, where the Tatmadaw has been slowly hollowed out, there is greater reliance on the pro-junta Pyu Saw Htee militia.

ロシアもミャンマーも、訓練が不十分な徴兵制の軍隊に頼っており、士気も低い。ロシア軍は死傷者や脱走によって減少しており、指導者はチェチェンやシリアから傭兵を呼び寄せたり、ロシアの準軍事組織である自国のワグネル・グループを呼び寄せたりしている。ミャンマーでは、タッマドーが徐々に空洞化し、国軍支持の民兵組織Pyu Saw Hteeへの依存度が高まっている。

Russia has imposed almost a total blackout of media not under state control, forcing most foreign reporters from its borders. Russia is transforming its internet into a Chinese-style intranet. In Myanmar, there have been attempts to shut down the internet in the conflict-wracked regions like Sagaing to prevent evidence of government atrocities, while policing social media to target dissent. In both countries, the assaults and arrests of journalists continue apace. As in the towns and cities that the Russians occupy, the Myanmar military has been summarily executing civilians.

ロシアは国家の統制下にないメディアをほぼ完全に遮断し、ほとんどの外国人記者を国境から追い出し、インターネットを中国式のイントラネットに変えつつある。ミャンマーでは、政府の残虐行為の証拠を防ぐために、サガインなどの紛争地域でインターネットを遮断しようとする試みがあり、一方で反対意見を標的にソーシャルメディアを取り締まろうとしている。両国で、ジャーナリストへの暴行や逮捕が後を絶たない。ロシアが占領している町や都市と同様に、ミャンマー軍も民間人を即座に処刑している。

The leadership of both countries believe that if they act with enough violence they can submit the civilian population to their will and will be able to evade all accountability. In recent fighting in Myanmar, over five dozen civilians were burnt to death. Neither government tries to hide their war crimes; indeed they want them there for all to see, as a warning of things to come.

両国の指導者は、圧倒的な暴力をもってすれば民間人を自分たちの意思に従わせることができ、あらゆる説明責任から逃れることができると考えている。ミャンマーでの最近の戦闘では、60人以上の民間人が焼き殺された。どちらの政府も自分たちの戦争犯罪を隠そうとしない。むしろ、来るべき事態への警告として、誰もが見ることができるようにしたいのだろう。

Both regimes are sanctioned, and have seen much of their trade diminish

両政権とも経済制裁の結果 貿易の多くが減少している

There is a shared belief that they can weather international sanctions and both governments are displaying callous disregard for the economic crisis that they are causing their populations. Both have quickly reversed over a decade of economic progress. The junta in Myanmar oversaw an 18 percent contraction of the economy in 2021, and more than half the population now lives in poverty. Today the citizens of Yangon are experiencing electric shortages and a lack of water.

両政府は、国際的な制裁を切り抜けられると信じており、自国民に与えている経済危機を非情にも無視している。両国とも、10年以上にわたる経済的進歩をあっという間に覆した。ミャンマーでは2021年に18%の経済縮小、人口の半分以上が現在貧困の中で暮らしている。今日、ヤンゴンの市民は電力不足と水不足に見舞われている。

The wars in both countries have seen incredible courage against all odds. We’ve witnessed valiant fighting by Ukrainians defenders as well as by Myanmar’s People’s Defense Forces (PDFs) and their allied Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs). But they are up against insurmountable odds. Even if the Tatmadaw has a smaller fighting force than is often suggested, it is still larger and better resourced than the PDFs, with the power of conscription.

両国の戦争では、あらゆる困難に対し勇気ある行動も見られる。ミャンマーの人民防衛軍(PDF)とその同盟組織である民族武装組織(EAO)、そしてウクライナ人防衛兵の勇敢な戦いを世界は目の当たりにしている。しかし、彼らは乗り越えられない困難に直面している。タッマダドーの戦闘力は一般に言われているよりも低いとはいえ、PDFより大きく、予算も資源もある。

The PDFs continue to have significant challenges in raising funds and acquiring arms and ammunition. Recently we’ve seen several battles that have left about dozen PDF personnel killed having run out of ammunition. The NUG just announced that their PDFs will have a $30 million budget this year. While that’s significant amount for sub-state militia, it is paltry compared to the resources of the Tatmadaw. Just through their asymmetrical dominance in materiel, the Russian military and the Tatmadaw are able to grind out a long war.

PDFは現在、資金調達や武器・弾薬の獲得が困難な状態となっている。最近では弾薬を使い果たし、十数名の兵士が死亡する戦闘が何度か発生した。NUG国民統一政府は、今年のPDFの予算を3,000万ドルにすると発表した。民兵組織としてはかなりの額だが、タッマドーの資源と比べれば微々たるものである。ロシア軍とタッマドーは、物資の非対称性で優位に立つだけで、長期戦に持ち込むことができるのだ。

Like the Ukrainian forces, the PDFs and their affiliated EAOs have high morale, relatively good discipline, and a just cause that they are fighting for. They hold themselves to higher standards on the battlefield in terms of trying not to commit war crimes, intentionally target civilians, or looting and pilfering. And unlike the Tatmadaw or the Russians, they enjoy overwhelming popular support.

ウクライナ軍と同様に、ミャンマーの人民防衛軍PDFは高い士気と比較的良好な規律、そして戦うべき正当な理由を持っている。戦場では、戦争犯罪や意図的な民間人襲撃、略奪などを行わないという点で、より高い基準を設けている。そして、タッマドーやロシア軍とは異なり、圧倒的な民衆の支持を得ている。

Right: Myanmar’s junta chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, who ousted the elected government in a coup on February 1, 2021, presides over an army parade on Armed Forces Day in Naypyitaw, Myanmar, March 27, 2021. Credit: Reuters. 写真右: 2021年2月1日にクーデターで、選挙で選ばれた政府を追放したミャンマーの軍政長官ミン・アウン・フライン上級大将。2021年3月27日にミャンマーのネピドーで武装勢力記念日の軍隊パレードを主宰している。

In both cases, the way the conflicts likely end is from within

どちらの場合も 紛争が終わる可能性が高いのは内部から

In Russia, the oligarchs may not pose a challenge to President Vladimir Putin simply because they do not control any coercive instruments. The threat Putin faces comes from his own security services, which he appears to be scapegoating for the military’s poor performance.

The real threat to junta leader Min Aung Hlaing and his deputy Soe Win comes from lower-ranking generals and colonels who have not shared in the military regime’s spoils. These are the people who have to execute the war and who understand that given the rate of casualties and defections that they do not have the manpower to hold territory. These are the people that know how despised the military is and how little legitimacy its regime has. They are the people who know that the war is unwinnable and have an interest in protecting what’s left of the military’s political, economic, and institutional interests. They know they can only do that through a negotiated settlement and that is impossible with this senior leadership still in place.

ロシアでは、オリガルヒ(ロシアの新興財閥)がプーチン大統領に挑戦状を叩きつけることはないかもしれないが、それは彼らが強制的手段を持っていないからである。プーチンが直面している脅威は、ロシア軍のパフォーマンスの低さの責任を転嫁されているプーチン自身の大統領警護局(SBP)であろう。

ミャンマー軍事指導者に対する真の脅威は、軍事政権から利益を得ていない下級将官や大佐たちである。彼らは戦争を遂行しなければならず、死傷者や離反者の割合からして、領土を維持するための人員がないことを理解している。軍がいかに軽蔑され、その政権の正当性がいかに低いかも知っている。この戦争に勝ち目がないと知りつつ、軍に残された政治的、経済的、制度的利益を少しでも守りたいと考えている。交渉による解決を目指すしか道はないが、ミン・アウン・フラインがトップに居続ける限りそれは不可能であると、彼らも知っている。

Zachary Abuza is a professor at the National War College in Washington and an adjunct at Georgetown University. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of the U.S. Department of Defense, the National War College, Georgetown University or RFA.

ザカリー・アブザはワシントンのナショナル・ウォー・カレッジの教授で、ジョージタウン大学でも非常勤講師を務めている。ここで述べられた見解は彼自身のものであり、米国防総省、国立戦争大学、ジョージタウン大学、RFAなどの立場を反映するものではありません。